Let There Be Light (and Space): Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego Reopens After $105 Million Selldorf Renovation

Source: Artnet

The overhaul allows the museum to finally show off its collection, rich in 1960s-era works and women artists.

When the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego (MCASD) began its collection, Southern California had a dearth of institutions for contemporary art. It was at MCASD that a then-barely-known John Baldessari had his first exhibition, in 1960—eight years before he showed in a commercial gallery, and four years before the Los Angeles County Museum of Art hired its first modern art curator. Founded in 1941, right on the beach in La Jolla, MCASD had devoted itself to collecting art of the 20th century by the end of the 1960s, making it the longest-lived contemporary art institution between La Jolla San Francisco (the Pasadena Art Museum didn’t survive the 1970s, and MOCA L.A. wasn’t founded until 1979). Yet MCASD, even as it filled a void amid the region’s postwar creative ferment, has lacked the space to permanently display its 5,600-work collection until now.

The museum, which reopened on April 9 after a four-year closure and a $105-million renovation, is finally equipped to showcase its history. “If folks came down to see the special exhibition of Jack Whitten, that’s what they would see,” explained MCASD director Kathryn Kanjo, referring to a Whitten show the museum staged in 2014. Alternatively, if the museum installed highlights from its collection, which it began building in the 1960s, it couldn’t stage a special exhibition.

Aerial view of MCASD’s new La Jolla flagship by Selldorf Architects. Courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. Photo: Breadtruck Films.

Renovation was already a priority when Kanjo, who had worked at MCASD as a curator in the 1990s, came back as deputy director in 2010. “That was part of the appeal of returning, knowing that there was a commitment to expand the gallery spaces,” said Kanjo, who previously directed the University of California, Santa Barbara Art Galleries. When she arrived back in San Diego, she first served under director Hugh Davies, who had helmed the museum since 1983. Davies retired in 2016, and Kanjo took over. At that point, the museum had selected architect Annabelle Selldorf, whose work for gallery and museum clients privileges subtlety over theatrics, to reimagine its architecture.

The original Irving Gill façade at MCASD’s new La Jolla flagship by Selldorf Architects. Courtesy of Selldorf Architects. Photo: Nicholas Venezia.

Selldorf had her work cut out for her, as MCASD’s facilities reflected multiple generations of architectural interventions. The museum’s history began when, in 1941, the founding trustees purchased the building—the former home of late philanthropist Ellen Browning Scripps—for $10,000. Designed by early Modernist Irving Gill, whose elegant buildings (many now demolished) spread between Los Angeles and San Diego in the 1910s and ’20s, the original structure was an artifact of architectural innovation in Southern California. It was also “fundamentally residential in scale,” as Selldorf pointed out—a fact that poses challenges for a 21st-century contemporary art museum. Other architects had tried to address these shortcomings. In 1950, Robert Mosher and Roy Drew expanded the home to include formal galleries before adding an auditorium, and in 1996, Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates restored the original house and added the Axline Courtyard, a hall named after donors, a café, and a sculpture garden. The building remained essentially Californian, but if Gill represented a subtle approach to low-to-the-ground coastal architecture, Venturi Scott Brown—known for embracing the idiosyncrasies of vernacular architecture—were especially attuned to the eclectic aesthetic of the sprawling region. Their addition did not add any gallery space.

The entrance at MCASD’s new La Jolla flagship by Selldorf Architects. Courtesy of Selldorf Architects. Artwork: Andy Goldsworthy, Three Cairns (2002). Photo: Nicholas Venezia.

“I’ve always felt that the Irving Gill building that really got it all started was very, very important,” said Selldorf, “and that, while Venturi Scott Brown had very lovingly restored that building, they also kind of layered something else on top of it.” Her task was to somehow unite the buildings while also respecting their distinct characters, which involved removing the almost comically thick columns with which Venturi Scott Brown obstructed the front of the Gill entrance (the columns are now down the street, at the La Jolla historical society).

“To me, there is a kind of neighborly relationship that we were able to institute between all of the disparate parts,” said Selldorf, whose design doubled the museum’s square footage and quadrupled the amount of gallery space while creating a circular traffic pattern between the earlier buildings and the new. “I think about circulation a lot,” said Selldorf, “because I think that if you go to a museum, you want to both be able to capture it all, but you also don’t want to be told what to do.”

The Sahm Seaview Room and Bartell Terrace with views of the Pacific Ocean at MCASD’s new La Jolla flagship by Selldorf Architects. Courtesy of Selldorf Architects. Photo: Nicholas Venezia.

Selldorf also wanted to ground the museum experience in the specificity of its surroundings, situated between the Village of La Jolla to the east and epic ocean vistas to the west. To this end, windows play a key role, though not in the way she initially imagined. “When we started working on the museum, I thought, ‘Everything is about daylight,’” explains Selldorf. “This incredible Southern California light was something I was awed by, only to learn that it’s actually very difficult to harness.” Instead of the open-air courtyards she envisioned, light comes in more subtly. Throughout, narrow floor-to-ceiling windows grant viewers unobstructed glimpses of the surroundings. Other galleries let the environment in more completely, such as the gallery with a slatted skylight covering the entire ceiling. Kanjo, working with associate curator Anthony Graham, has filled this particular gallery with SoCal Light and Space work by the likes of Robert Irwin, Mary Corse, and Larry Bell.

Installation view of the Foster Family Gallery at the newly expanded MCASD by Selldorf Architects. Courtesy of Selldorf Architects. Artwork left to right: Dorothy Hood, Earth Bolts (1974), Sol LeWitt, Six-Part Modular Cube (1976), Ellsworth Kelly, Red Blue Green (1963), Miriam Schapiro, Big Ox No. 2 (1968), Frank Stella, Sinjerli 1 (1967). Photo: Nicholas Venezia.

In her rehang of the permanent collection, Kanjo tried to emphasize this 1960s legacy, a strength of the museum’s holdings. The new galleries start with California Light and Space, followed by a room full of abstraction, much of it––including the epic paintings by Helen Frankenthaler and Ellsworth Kelly—collected by San Diego surgeon Jack Farris and his wife, Carolyn, in the 1960s and 1970s. Then, once you’ve circled all the way around, you’ll encounter California assemblage by Ed Kienholz and Daniel LaRue Johnson. Kanjo has taken care to contextualize the Californians, too, as in a basement gallery that combines work by Los Angeles artists Helen Pashgian and Doug Wheeler with East Coast Minimalists like Donald Judd. “On one hand, they’re very much about San Diego or Los Angeles, what’s happening on the West Coast,” said Kanjo, “but it’s also that reductive, geometric, Minimalist approach that is happening in other places but with different materials.”

Installation view of the Marshall Gallery and Cohn Gallery inside MCASD’s new La Jolla flagship by Selldorf Architects. Courtesy of Selldorf Architects. Artwork from left: Lari Pittman, How Sweet the Day After This and That, Deep Sleep Is Truly Welcomed (1988), Andy Warhol, Flowers (1967). Photo: Nicholas Venezia.

Kanjo also tried to tell a more open, diverse story of postwar art in her selections, something the collection—heavy in work by women, and by Latin American artists who work on either side of the California-Mexico border—facilitated. “We’re telling a rich history as much as possible through our collection, and frankly, I’m rather proud of the institution’s track record,” Kanjo said. Women make up 40 percent of the artists in the reinstallation of the permanent collection, and the first abstraction gallery, dominated by Dorothy Hood and Nancy Graves in addition to Frankenthaler, features more women than men. The gallery overlooking the biggest ocean-facing windows highlights artists engaged with the San Diego-Tijuana border. The intersections of folk art, Pop, and Conceptualism come to the fore in such works as Felipe Almada’s The Altar of Live News (1992), a colorful cabinet combining ritual objects with plastic souvenirs and news clippings chronicling the political and economic realities of the border. “With the upheaval and social reckoning over the past few years, we’re mindful about the role we play, what kind of authority we bring, and about the story we’re telling,” said Kanjo.

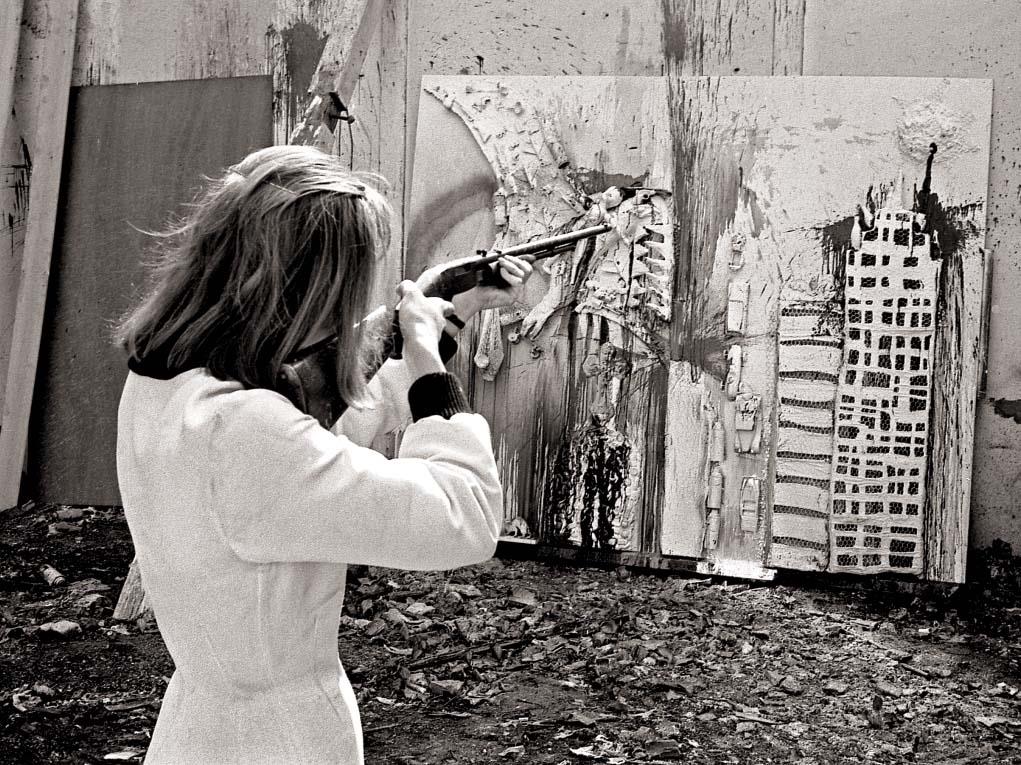

Niki de Saint Phalle during a shooting session at Impasse Ronsin, Paris, 1962. © André Morain.

The MCASD’s special exhibitions will be similarly attentive to the story that they tell, continuing to feature women with a connection to the region across this first year. The new special-exhibition galleries (which Selldorf set in the former 1950s auditorium, to make good use of tall ceilings that predate La Jolla Village’s height restriction) debut with “Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s.” It coincides with an exhibition, at MCASD’s downtown offshoot, of work by Yolanda López––the late Chicana artist-activist’s first, much-overdue museum solo show. And in September, the museum will pay tribute to Alexis Smith, whose ambitious, 62-foot-long mural depicting the wide-open California highways as a snake, The Same Old Paradise, is newly restored and installed at UCSD.

But it is “Niki De Saint Phalle in the 1960s” that crystallizes the museum’s potential, underscoring the importance of Southern California as a site for 1960s experiments, while also telling a much wider story about proto-feminism and an international turn toward social awareness among artists. Curated by MCASD’s Jill Dawsey and Michelle White of the Menil Collection, the show features under-exhibited work by the Paris-born, New York-raised artist, who spent her last decades in La Jolla, hoping the ocean air would help her health, ravaged by years wielding toxic chemicals. Vintage footage in the galleries shows Saint Phalle in the Malibu Hills, making one of her Tirs, in which she shot at her own ambitious assemblages loaded with paint. Ed Kienholz hands Saint Phalle her rifles and uses a rag to wipe pigment off her face as she shoots, color exploding from the jars and other objects encased beneath plaster. This performance, and another one staged off the Sunset Strip, exposed resonances between the West Coast assemblage artists and those working elsewhere. “As a matter of fact, all the critics are against me except my fellow artists,” Saint Phalle said of this time. She found allies in Southern California.

Link to Original Article (may require registration)

https://bit.ly/3spIA41